The 10 Best Frazier Weekly Articles of 2024

Each Monday at 7 a.m., we send you a new issue of Frazier Weekly—chock-full of original articles, videos, and interviews, contributed by Frazier staff members.

But today, we’re taking the week off!

So to tide you over we’ve compiled the ten best Frazier Weekly articles of 2024, arranged by date of publication.

Before we look back at the best of last year, we’ve got three announcements about 2025.

First, we’re temporarily adjusting our hours of operation: during January, the museum and museum shop will be closed on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. But don’t worry: starting February 1, we’ll go back to operating seven days a week.

Second, our first program of the year takes place later this month. Join us Thursday, January 30, for Personal Impact: Finding Common Ground on Guns. Mike Campbell, Rose Smith, Whitney Austin, and Maryanne Elliott will share the personal impact gun violence has had on their lives.

Last, our February 13 program For the Love of John Prine has sold out! A folk musician, John Prine (1946–2020) spent his childhood summers in Muhlenberg County, Kentucky. We look forward to hosting a celebration of his life and music.

As always, thanks for reading. If you enjoy Frazier Weekly, please tell your friends, family, and colleagues to subscribe.

Happy new year!

Simon Meiners

Communications & Research Specialist

Frazier History Museum

The Ten Best Frazier Weekly Articles of 2024

Published in the February 12, 2024, issue.

When our ancestors came to Appalachia, they brought with them a rich history of courtship from their mother countries. Coupled with the difficult conditions and ingenuity required to live in the rugged mountains, a unique code of courtship was created.

Appalachian oral history has numerous sayings about courtship:

If you name a fish hook after your sweetheart and then you catch a fish with that hook, the love is true.

If you itch, you want to be kissed.

If you tuck a four-leaf clover inside of your shoe, you will marry the next person you see.

If two people dip their spoons in the same cup at the same time, they will be married.

Communities were mostly isolated by the mountainous and rugged terrain, making it difficult to court someone from other communities, who were considered “outsiders.” Couples mostly met close to home, usually at school or at church. Because of the geographical seclusion, could be “slim pickin’s” in the community, making competition fierce for unmarried girls.

The church played an important role in courting. Frequently, courting began with a young man walking a young girl to church. Other ways of meeting were barn dances, fairs, and community picnics.

Appalachian dulcimer. Credit: folkart.com.

Appalachian love spoons. Credit: CBS News.

Courting was not usually a long affair, often lasting just a few weeks or months. The young man would bring gifts to the family, a custom known as “sparkin.” The preservation of a young girl’s chastity meant that the couple must be supervised at all times. One way for the young couple to be alone was by playing the courting dulcimer. The dulcimer is a stringed instrument that is played by strumming. The courting dulcimer allowed for the couple to play the dulcimer simultaneously. As long as adults heard music playing, they were assured that the young couple was remaining chaste. If a couple played the dulcimer well together, it was believed that they would make beautiful music in a marriage.

Once a young man decided to propose, he might show his romantic intent with the Welsh custom of carving a love spoon. These wooden spoons were often designed with Celtic knots, hearts, and wheels. Other elements included bells that signified marriage, crosses for faith, and locks for security. A love spoon demonstrated to the girl and her family that the young man was capable of supporting her.

The double wedding quilt has a rich tradition in Appalachia. Oral storytelling explains that a soldier was injured in the Civil War and his wedding was delayed. When he finally returned home, he was without rings for the ceremony. The grandmother of the bride had made a quilt of circles and she offered it to the couple as a symbolic representation of wedding rings.

Women of the community had their own ritual involving the wedding ring quilt, gathering in quilting bees to create them. When a quilt was finished, the single girls in the community would hold the corners of the quilt, put a cat in the middle of the quilt, and shake the quilt. Whatever corner of the quilt that the cat ended up on revealed the next girl to be married.

When a couple married, it was commonly at the family home. The community came together to “make” a wedding. One of the ways was to make the wedding cake communally. Ingredients were scarce and expensive. Wedding guests would each bake one layer, which would be stacked together, creating a stack cake, typically with a dried apple filling.

The customs of courting and marriage in Appalachia are rich in cultural heritage. Through storytelling and oral histories, people of Appalachia found a way to keep their histories and traditions alive in spite of challenging circumstances.

Susan Reed

Stories in Mind Facilitator

Published in the February 12, 2024, issue.

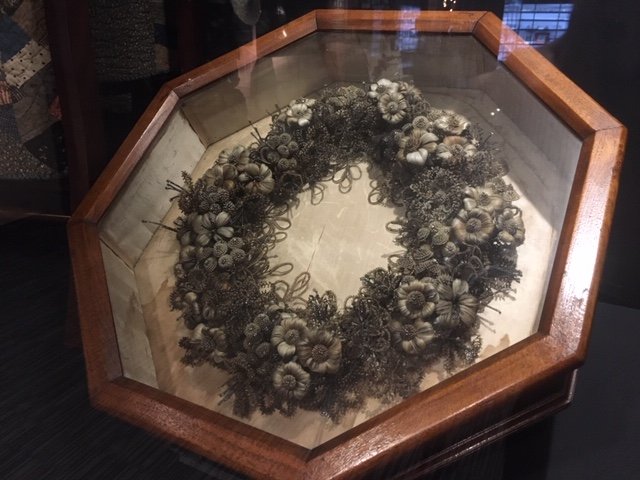

Victorian hair wreath made c. 1875. On display in the Frazier’s Founder’s Gallery.

In early March, the Frazier Museum will retire a nineteenth-century hair wreath from display in the second-floor Founder’s Gallery. Many who pass by this unique specimen are unaware of the medium, and it is fair to say that many feel an adverse reaction upon learning that this wreath is composed of human hair. Yes, that’s correct: this delicate and beautiful artwork in our collection is made of hair. While this tradition seems odd, macabre, or even creepy today, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, hairwork jewelry and crafts were wildly fashionable and directly linked to Victorian notions of sentimentality and romanticism. Victorians embraced hairwork as a form of art, and sharing hair with friends, family, and loved ones was a beautiful expression of love and friendship. Consider this quotation from a popular women’s magazine of the Victorian Era:

“Hair is at once the most delicate and lasting of our materials and survives us like love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that, with a lock of hair belonging to a child or friend, we may almost look to Heaven and compare notes with angelic nature, may almost say: ‘I have a piece of thee here, not unworthy of thy being now.’—Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1860

The popularity of hairwork jewelry is a direct result of high mortality rates and the desire to commemorate and remember lost loved ones. During the height of this period, average life expectancy was forty years, and women had a one in thirteen chance of dying during childbirth. Illness and death often took place at home and, as a result, people had a different relationship with loss and mourning than we do today. Mourning etiquette was observed across the social spectrum, and women carried the burden of stricter rules and extended mourning periods. Queen Victoria famously mourned her late husband, Prince Albert, from the time of his death until her own death forty years later. She is also known to have commissioned several pieces of hairwork jewelry made with his hair so that he would remain close to her even in death.

That being said, not all hairwork was jewelry, nor was it exclusively linked to bereavement. Friends and family members often exchanged locks of hair as a sign of amity and affection. It can be a way to capture a nostalgic and tender moment, much as a parent today might preserve a lock of their children’s baby hair. By the nineteenth century, women’s magazines and periodicals offered lengthy explanations on how to create hairwork art at home. Hairwork became a popular drawing room craft, much like embroidery, knitting, and crochet. This is likely the origin of our own hairwork wreath. One historian stated that “Shadowboxes containing wreaths created from the hair of family members served as a family tree of sorts and could take years to complete, generation on generation adding on additional elements.”

I suspect that the hairwork wreath at the Frazier Museum is an example of a family tree—each flower a beautiful representation of a different member of the family. As this year’s Valentine’s Day approaches, you may not be convinced to gift a lock of hair to your partner; but I strongly encourage you to visit our Founder’s Gallery and see this sentimental, commemorative wreath before it goes off display March 4.

Leslie Anderson

Sr. Manager of Grants & Community Development

Published in the March 18, 2024, issue.

As the official starting point of the Kentucky Bourbon Trail®, the Frazier History Museum shares stories of the people, places, and producers of the Kentucky Bourbon industry. To learn more, visit our Kentucky Bourbon Trail® Welcome Center or tour our Spirit of Kentucky® exhibition.—Simon Meiners, Communications & Research Specialist

In today’s episode of Sippin’ with Stephen, I chat with my friend Sydney Disponett. Sydney is the Kentucky state sales manager for RD1 Spirits, located in Lexington. We discuss RD1’s core product offerings, distillery expansion, tourism opportunities, and the fact that RD1 is the next release in Bourbon Limited! Finally, Sydney highlights one of RD1’s signature cocktails, Lexington Lemonade.

Recipe for Lexington Lemonade

Ingredients:

2 oz. RD1 Bourbon

2 oz. lemonade

2 oz. orange juice

Instructions:

Pour ingredients into large pitcher and stir well. Serve over ice and garnish with an orange or lemon wheel. For those hot summer days, consider substituting frozen lemonade for a blended icy cocktail.

Stephen Yates

Community & Corporate Sales Manager

Published in the April 15, 2024, issue.

Moving forward, in each issue of Frazier Weekly, we are excited to share some of the incredible stories featured in our new exhibit 120: Cool KY Counties. As the 150th running of the Kentucky Derby is fast approaching, this week’s story sheds some light on horseracing traditions. Have you ever wondered why the Kentucky Derby, and other horse races in America, are run counterclockwise? It turns out that the answer goes back to some good old Kentucky stubbornness. You can learn more in Lincoln County’s story “Racing Counterclockwise.”—Amanda Briede, Sr. Curator of Exhibitions

Col. William Whitley House in Crab Orchard, Lincoln County, Kentucky, 1934. Photo by Theodore Webb. Credit: Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress.

Lincoln County was formed in 1780. It was one of Kentucky’s three original counties. Among the earliest colonists in the area were Col. William Whitley, his wife Esther, their children, and the enslaved people whom they owned. The Whitley’s enslaved people built the first brick house in Kentucky. It included a secret passage for escape and survival during raids by Native Americans. The home is now preserved as the William Whitley House State Historic Site.

The first circular horserace track in the state was also built on the Whitley plantation. Races at the track, known as Sportsman’s Hill, began in 1788. It had the first clay track in the United States. Prior to this, all racetracks featured a turf track. Also at the track, horses raced counterclockwise in opposition to the British tradition of racing clockwise. The American tradition of racing counterclockwise, which began in Lincoln County, continues throughout the United States today.

Published in the May 20, 2024, issue.

Megan Schanie’s employee head shot, c. August 2004.

In December 2003, when I accepted a part-time position in the education department of a new museum being planned for downtown Louisville, a lot was different: George W. Bush was president, Finding Nemo was the top movie, I owned a flip phone, and I was married with a ten-month-old baby girl. That new museum was to be called the Frazier Historical Arms Museum.

Twenty years and multiple museum name changes later, I’m happy to be a married mother of two nearly-adult daughters—a sophomore at U of L and a senior at WKU—and still plugging away on the Frazier’s education team.

In honor of the museum’s 20th anniversary, I’m excited to reflect and share 20 of my favorite Frazier exhibitions, programs, people, and memories.

Megan Schanie leads students through a gallery in the museum, 2012.

Growing Up! Wow, we have really changed over the years—from a historical arms museum created in partnership with the British Royal Armouries to the starting point of the Kentucky Bourbon Trail® and the place “where the world meets Kentucky.” Like any good journey, it was bumpy at times; but it’s been impressive to have an inside view of our transformation.

Faces Lighting Up. It’s not a stretch to say I’ve seen at least 200,000 young faces over the years come around the corner into the museum as we welcome them to their field trip, getting their first glimpse inside. What they’ve seen has changed over the years, from a knight and cavalry officer on horseback to a dragon in our Mythic Creatures exhibition, Napoleon’s bed, and now a red Corvette in Cool Kentucky. But the reactions are very much the same: wide eyes and talking with excitement to their friends. It’s fun to see the museum through young, fresh eyes each morning.

Adi Schanie’s Pirate Interview. My older daughter Adison is currently a reporter at WDRB news, and it all started right here at the Frazier Museum. As a third-grade student-reporter for the Bloom Elementary media club, she conducted her very first interview with female pirate Anne Bonny back in 2011.

Kids at Camp. It’s always fun to see kids at Frazier camp having a ball at the museum all day creating, playing, and learning. It’s especially fun when it’s your own kids, and you’re not in charge of camps. Both of my daughters spent many, many weeks having a terrific time at the Frazier growing up, enjoying all the activities but able to run into my office for a quick hug. They both will still tell you it was their favorite, especially performing skits in the theatre during “Page to Stage.”

Standing Ovation. In 2006, as a two-year Frazier employee and the mother of an infant and a toddler, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. Not only did the museum staff rally around me and give me all the support and time off I needed, they also created a safe haven of normalcy when I was well enough to return to work. I wore a scarf during chemo. One day, after I gave a field trip presentation, a young student raised his hand and asked why I was wearing the scarf. After I gave a brief explanation to the school group, the student just stood up and started to applaud. Then the rest of the students stood up with him and started to applaud. Can you imagine that? It was incredible.

Bird’s-Eye View of Muhammad Ali Funeral Procession. Being on the roof of the museum looking down at the expressway to watch the Muhammad Ali funeral procession drive by on June 10, 2016, was one of the most incredible things I’ve ever seen. The whole city seemed to pause that day in honor of Ali. As the hearse and other cars came past, slowly moving west after pausing outside the Ali Center, all of the cars on I-64 driving the opposite direction slowed to a complete stop as the procession passed by. It was a striking moment of respect to witness.

Nat Love. For many years, the life-size figure of Black cowboy Nat Love—surrounded by a saddle, chaps, and a taxidermy snake—was on a display in the American West gallery in our second-floor American History exhibit. Now that the display is down, Nat spends his days surrounded by books, children, and even an axolotl named Boba in the Marshall Foundation Education Center, where my office is. He’s a terrific addition to teaching and learning and one of my favorite things in the education center.

Fontaine Ferry Park Exhibition. It’s hard to pick a favorite exhibition. We’ve had some terrific ones over the years. But one of my early favorites was Fontaine Ferry Park. I grew up in Louisville yet had never heard of the park and knew nothing of its complex history. The exhibition taught me that seemingly “light” topics can share meaningful history and memories, and that when people have strong memories and connections to a place in their lives they will show up to reminisce, reflect, and share.

The Original Team. Thinking back has me reflecting on the many people, with varied skills and backgrounds, it has taken to bring us where we are as a museum today—from Mr. Frazier with his original vision to the architects, builders, museum board, opening staff, partner organizations, volunteers, and interns. And of course, I can’t forget the original guests and members who walked through our doors.

The “Creatives.” Many staff members have come and gone over my years at the museum, but I’ve always been surrounded by what I’d call “creatives”—musicians, photographers, singers, glass artists, story tellers, actors, and puppeteers—all doing double work with many other roles at the museum. They are the best to plan, brainstorm, and think outside the box with. They also make the workday fun!

Sword Fights in the Tournament Ring. When the Frazier first opened, a tournament ring was snuggled into the middle of the third floor as part of the Royal Armouries exhibition. Our actors presented a wide range of sword fights each day for guests and school groups. I have terrific memories of packing in over 100 kids at a time: they stood around the ring to watch the demonstrations. These were truly unique and fun experiences.

Coronavirus Capsule. When COVID-19 hit the US full force, Frazier staff were all called to the board room for one last meeting before the break to work from home. Not knowing what would happen, or how long it would last, our leadership team immediately decided to begin a daily electronic newsletter to share stories, videos, and interesting content that would begin the very next day. That newsletter continues to exist today as Frazier Weekly and it’s one of the positive things to grow out of that experience and help keep us connected to the community. The development of the Coronavirus Capsule was a large part of that initial project; that was invigorating to be a part of during a difficult time.

Cornhole. Did I mention that I was a member of team that won the inaugural Frazier Cornhole Tournament? I’ll admit my partner carried much of the weight, but I hung in there. With museum president Andy Treinen stepping in on the final day due to a sick partner, we finished on top. I grew up an athlete, but that’s the only tournament I’ve ever won.

Special Projects. Every now again we are approached with an “outside the box” idea for a large project with an outside partner and those usually end up being some of my favorite things to work on. Just to name a few we’ve hosted a “Teaching with Museums” summer course through the University of Louisville college of education, partnered with multiple schools and organizations on the Cool Kentucky Student Art exhibit, and worked with the Bullitt County Gifted and Talented program on a custom visit focused on the Underground Railroad.

Dragons, Documents, Disco Balls, and More. In 20 years, I’ve never been bored at the Frazier. You never know what you might see next—whether it’s excited kindergarteners dancing under the disco ball in Cool Kentucky, exhibits staff attaching the head to a dragon for our Mythic Creatures exhibit, or being invited into collections to view the newly-acquired Mary Todd Lincoln arrest papers—each new day brings something unexpected.

Incredible People. One perk of my job is exposure to incredible people who present or share artifacts or knowledge with the museum. I’ve met Tori Murden McClure, the first woman and first American to row solo across the Atlantic Ocean; Kentucky archaeologists Anne Bader and Gwynn Henderson are fascinating to talk to; and Karolyn Smardz Frost, author of I’ve Got a Home in Glory Land, our key source for The Journey, has become an amazing resource to the Frazier and the education team. From city historian Tom Owen to Kentucky poet laureate Frank X Walker and New York Times best-selling author Jermaine Fowler, incredible people walk through these doors every day.

Hiding Hamilton. When Hamilton: the Musical hit Louisville several years ago, we had a great time enjoying the fanfare at the museum with events, special programs, and even hiding a life-size Hamilton around the museum for guests to find.

Creating Programs. I love creating programs for students and teachers. It’s incredible to think about how many offerings our education team has pulled together over the years, trying all sorts of different techniques and formats. From “History in Miniature” to “Kentucky Pioneers,” “Declaring Your Independence,” and more—not to mention the programs that have aligned with our temporary exhibitions—it’s one of my favorite parts of my job.

The Journey. Some stories just stick with you. When our education team heard about Lucie and Thornton Blackburn and their escape from their enslavers in Louisville in broad daylight on Fourth of July weekend in 1831, we immediately wanted to know more. Luckily for us, archaeologist, historian, and author Karolyn Smardz Frost had literally written the book on them. Using her research and other sources, we spent multiple years working on various aspects of The Journey: Unsung Stories of the Underground Railroad—a project whose goal is to share the story far and wide. It’s one of the projects I’m most proud to be a part of.

West of Ninth. I followed the West of Ninth blog created by Walt and Shae Smith for a year or so before I had the opportunity to meet them in person. We were really impressed with their work, so we invited them to talk with our education and exhibits team about possible collaborations. That brief meeting led to West of Ninth: Race, Reckoning, and Reconciliation, a powerful exhibition the Smiths guest curated in 2021. This stands out as another of my favorite exhibitions over the years.

It’s not lost on me how unique it is to still enjoy a job with a team of smart, passionate people moving towards a shared goal—especially for 20 years. I feel lucky.

Happy 20th to the Frazier!

Megan Schanie

Sr. Manager of Educational Programs

Published in the June 10, 2024, issue.

US Navy shaving kit made c. 1860s.

Tish Boyer, about age five, helps her father shave his beard, 1985! Credit: Tish Boyer

This week from the collection, we wanted to look at something to celebrate Father’s Day. In 1908, Spokane, Washington, native Sonora Smart Dodd tried to establish an official holiday for fathers in honor of her own father, a single parent to six children. However, unlike Mother’s Day, Father’s Day took a long time to catch on. The lack of enthusiasm for the holiday was often chalked up to the idea that fathers were less sentimental than mothers.

By World War II, however, efforts were renewed by advertisers who argued that celebrating Father’s Day was a way to honor the troops and support the war effort. While this still did not make the day a federal holiday, it did solidify it as a national institution. In 1972, President Richard Nixon signed a proclamation making Father’s Day a federal holiday which we now celebrate ever year in June.

In honor of Father’s Day, I thought it would be fun to share a memory I had of my dad that related to an object in our collection.

Most of my life, my father wore a full beard. He preferred the beard and I have only one memory of ever seeing him without it. When I was roughly five years old, my father was still in the Navy and regulations had changed, meaning he had to shave his beard. Since we were just small children, my dad didn’t want me and my brother and sister to fear him or not know who he was—so he let us “help” him shave. We got to use our scissors and help cut off the hair. We got to hand him the shaving cream can, and I remember sitting on the sink watching him as he shaved off his beard. Of course, once he was done, my sister grabbed her small Elmer’s glue bottle and a handful of the hair and asked him to put it back on. What a hard lesson to learn that hair takes time to grow, and you can’t just glue it back on!

From our collection, we would like to show off our 1860s US Navy shaving kit—complete with a small mirror, a shaving cream brush, soap, a lather cup, and a straight razor. These cool objects are currently on view in the Civil War gallery in our Commonwealth: Divided we Fall exhibition.

Come on down on Father’s Day and have a look at it.

Tish Boyer

Registrar & Manager of Collections Engagement

Published in the June 17, 2024, issue.

Gen. Gordon Granger, c. 1860–70. Credit: Civil War Glass Negatives, Library of Congress

On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, and officially issued General Order No. 3. This proclamation, backed by the presence of Union soldiers in Texas, brought an official end to slavery in the Southern state. The date has been recognized as Juneteenth, the holiday marking the end of legal slavery in America. Juneteenth became an official federal holiday in 2021.

Granger, the man who made the momentous declaration official, was Union Commander of the Department of Texas, a New York Democrat, and a career soldier. He also happens to be buried in Lexington Cemetery in Fayette County, Kentucky. After the war, he married a Lexington woman named Maria Letcher. When Commander Granger was not serving elsewhere on military matters, the couple spent a significant amount of time in the Commonwealth. Eventually, it was decided they’d spend eternity here as well.

Here’s how the June 19 General Order No. 3 reads:

The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

It was clear that no real assistance could be offered until the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Nevertheless, celebrations began that day.

Mick Sullivan

Curator of Guest Experience

Published in the August 12, 2024, issue.

Project Zomboid box art. Credit: the Indie Stone.

Side-by-side comparison of aerial maps of Iroquois Park, in real life and in the game Project Zomboid. Credit: Google Earth; Project Zomboid Project.

At the Frazier, we like to say that we’re where the world meets Kentucky. But gamers around the globe are getting familiar with our state through what might sound like an unlikely source: Project Zomboid, a zombie survival video game developed by the Indie Stone and available for PC through Steam.

Solo or with friends, players navigate a post-apocalyptic version of Kentucky that is overrun by the living dead. Project Zomboid is an open-world game with only one real goal for the player: survive for as long as possible, by any means necessary.

The events of the game take place in “Knox Country,” a partially fictionalized area of Kentucky that spans the real-world locations of Meade, Hardin, Jefferson, and Bullitt counties. Featured prominently are the real cities of Muldraugh, West Point, and Louisville.

The team at the Indie Stone did a remarkable job translating the real-life geography, street plans, and points of interests of these locations into their in-game counterparts. The cities are condensed, but the accuracy and attention to detail is clear when you compare the isometric Project Zomboid map to satellite images of the same places in Kentucky.

Intrepid survivors can start in Muldraugh or West Point, fight their way through the hordes on their way up Dixie Highway, make a pit stop in Valley Station, and then brave the horrors of overrun Louisville.

While their version of Louisville is scaled down to fit to the game’s map, the developers at the Indie Stone took a lot of inspiration from the city’s real-world layout. In the game, you can explore approximate versions of places like Iroquois Park, Slugger Field, Speed Art Museum, Cave Hill Cemetery, and a horse track with the suspiciously familiar name of “Chapelmount Downs.”

Being densely populated, Louisville is teeming with the undead, and many players of Project Zomboid consider the city to be the “end-game” location because of how difficult it is to survive in the city. The game has generated interest about real-life Louisville amongst its international fanbase. Some are even surprised to learn that it isn’t just a location invented for a video game! People who have never visited the US are able to get a feel for the things like the paths of Iroquois Park from the comfort of their gaming chair.

“THIS IS HOW YOU DIED” is the ominous title screen that greets players when they start a new game. But as a Kentuckian, I’d like to think Project Zomboid is showing people around the world a little bit about how we live.

Sarah Jemerson

Education & Engagement Lead

Published in the August 12, 2024, issue.

What a historic win for two runners with Team USA in the 1500 m race! Cole Hocker won gold and Yared Nuguse in a photo finish won bronze. The last time American runners swept medals like that in the US Olympic 1500m final was apparently back in St. Louis in 1904. Nuguse, known lovingly as “the Goose,” attended Manual High School and is a beloved figure in our community. Images of his win flooded my Facebook feed and I was there for it. And more joy in Kentucky as American fencer Lee Kiefer made history with her haul of gold. And no one beamed more about Lee than her grandmother, who lives in Louisville. Our Stories in Mind facilitator Jason Berkowitz met her as part of our engagements in the community. Her story and how she came to America helps us understand the “gold” standard of her entire family.—Rachel Platt, VP of Mission

Lee Kiefer’s grandmother Dr. Teresita Bacani-Oropilla, center, poses with, from left, the Frazier’s Jason Berkowitz and Kevin Bradley and WHAS11 journalists, July 31, 2024.

Last week, four-time Olympian and Lexington’s own Lee Kiefer won her third Olympic gold medal in women's team foil—the first such medal for the US in this event! Having already won individual gold in Paris, Lee is now the first American woman to win two fencing golds at the same Olympics. She is also now the first American, man or woman, to win three Olympic golds in fencing (including her individual gold in Tokyo)! Lee’s achievements will remain a source of pride for Kentuckians for years to come.

That said, there is no Kentuckian prouder of Lee and what she has accomplished than her very own grandmother, Dr. Teresita Bacani-Oropilla. Please allow me to share with you why Teresita is a champion in her own right—and an inspiration to not just Kentuckians, but people struggling against adversity the world over.

In December 1941, the Japanese military began bombing the Philippines, forcing many to flee densely populated areas such as Davao City. Among the thousands of refugees was twelve-year-old Teresita, separated from her family and seeking shelter under coconut trees to avoid being seen by enemy aircraft. Deeper and deeper into the jungle she and others escaped. There, Teresita stayed in hiding for nearly three years until eventually reuniting with her family (and also discovering she had a new baby sister).

However, it was when an eighteen-year-old Teresita decided to practice medicine that she set her family’s course for generations. Graduating from the Dominican University of Santo Tomas in Manila, Teresita started practicing as a pediatrician, treating patients from surrounding areas who lacked proper medical care. Tropical diseases and malnutrition were rampant. Modern medicine was practically non-existent. Yet, Teresita remained steadfast in her mission to serve the people of the Philippines, giving every ounce of her being to her indispensable work and undeniable calling. She continued doing so for fourteen years, while also traveling to the US to complete her residency at the University of Louisville.

During this time, Teresita entered into a relationship with a talented engineer named Ricardo Oropilla. The couple eventually married, though they and their two children, Joseph and Teresa, were forced to leave the Philippines as Communism spread in the region. With only $1,500 and a suitcase to their name, Teresita’s family began pursuing the American Dream, ultimately becoming a powerful testament to the vital role immigrants play in making the US the best version of itself.

Teresita went on to study psychiatry at the University of Louisville, completing her second residency at Central State Hospital. By now, she had dedicated herself and her work to two of society’s most vulnerable groups: emotionally disturbed children and veterans. Perhaps unsurprisingly, her children, Joseph and Teresa, followed Teresita into the medical profession, as did her six grandchildren—including Lee. I suspect the family’s legacy will only continue to grow and that this remarkable journey, started so many years ago in the Philippines, will never truly end. Indeed, Dr. Teresita Bacani-Oropilla challenges each of us to pursue our own dreams through hard work, dedication, and, most importantly, compassion. “Make use of your abilities,” she implores us. So whatever your light may be, let it shine for the world to see!

Learn more about Teresita in this WHAS11 news feature.

Jason Berkowitz

Stories in Mind Facilitator

Published in the October 21, 2024, issue.

It’s spooky-scary season, which means every house on the block is putting a jack-o’-lantern on the front porch. Our household, in attempting to maintain our place in a functioning society, is participating as well. This year, though, our daughter is old enough and interested enough to take the reigns of the pumpkin carving. So here are a few helpful tips from a young Halloween enthusiast for how to get festive this fall.

Step 1: Choose the right pumpkin. It should be roughly as wide as your entire body and heavy enough that you can barely lift it.

Step 2: Snack break. Picking up that pumpkin was hard! I recommend some peanut butter on toast to balance your carbs and proteins.

Step 3: Gather all the tools you’ll need. Trust me, you don’t want to be looking around for a bowl while you’ve got a handful of slimy pumpkin goop dripping everywhere. A big knife is also important, just be careful when you’re holding it.

Step 4: Let your dad do some work while you finish your snack. He likes to feel involved, and the inside of the pumpkin is kind of gross anyway.

Dad Tip: Cut the top off the pumpkin at a 45-degree angle so it doesn’t fall straight through the hole. Cut it in a hexagonal shape rather than a circle to keep the top from spinning once it’s back in place.

Step 5: Draw the face. Make it a little scary, but not too scary in case a baby sees it. Also, pumpkins usually have triangles for noses.

Step 6: Go play for a while. Pumpkin carving can get a little boring, so take an opportunity to do something more fun like making coffee for your stuffed animals. While you’re gone, the face you drew on the pumpkin will turn into holes. It’s like magic, how cool!

Now your jack-o’-lantern is done, so just light a candle inside and admire your creation. And if you decide it still needs a few more last-minute details, you’ve always got time to draw on some hair.

Happy Halloween!

Kent Klarer with his Daughter Frankie

Sr. Manager of Youth Programs & Education Advancement