History of Burgoo and Horseracing, 1980 Hot Pink Chiffon Suzy Creamcheese Gown, Emily Bingham on “My Old Kentucky Home,” and More

It’s Derby week, y’all, with Mother’s Day celebrations closing fast, right behind. The Kentucky Derby is always the first Saturday in May. Mother’s Day is always the second Sunday in May. Since this year May 1 falls on a Sunday, there you go: the first full weekend in May looks like a Superfecta for memory-making Kentucky fun.

Mother’s Day became an official holiday in 1914 when President Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation designating the second Sunday in May a day to honor our nation’s mothers. That was thirty-nine years after the first Kentucky Derby, when Aristides and African American jockey Oliver Lewis crossed the line two lengths ahead of Volcano.

With that, the Sport of Kings was born! Have fun with it this week—but, if you want to stay far clear of the doghouse, make sure the Queen of Your Household is priority number one.

Garland of roses presented to 2005 Kentucky Derby winner Giacomo, March 18, 2022. The object is on display in the Frazier’s Cool Kentucky exhibition. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

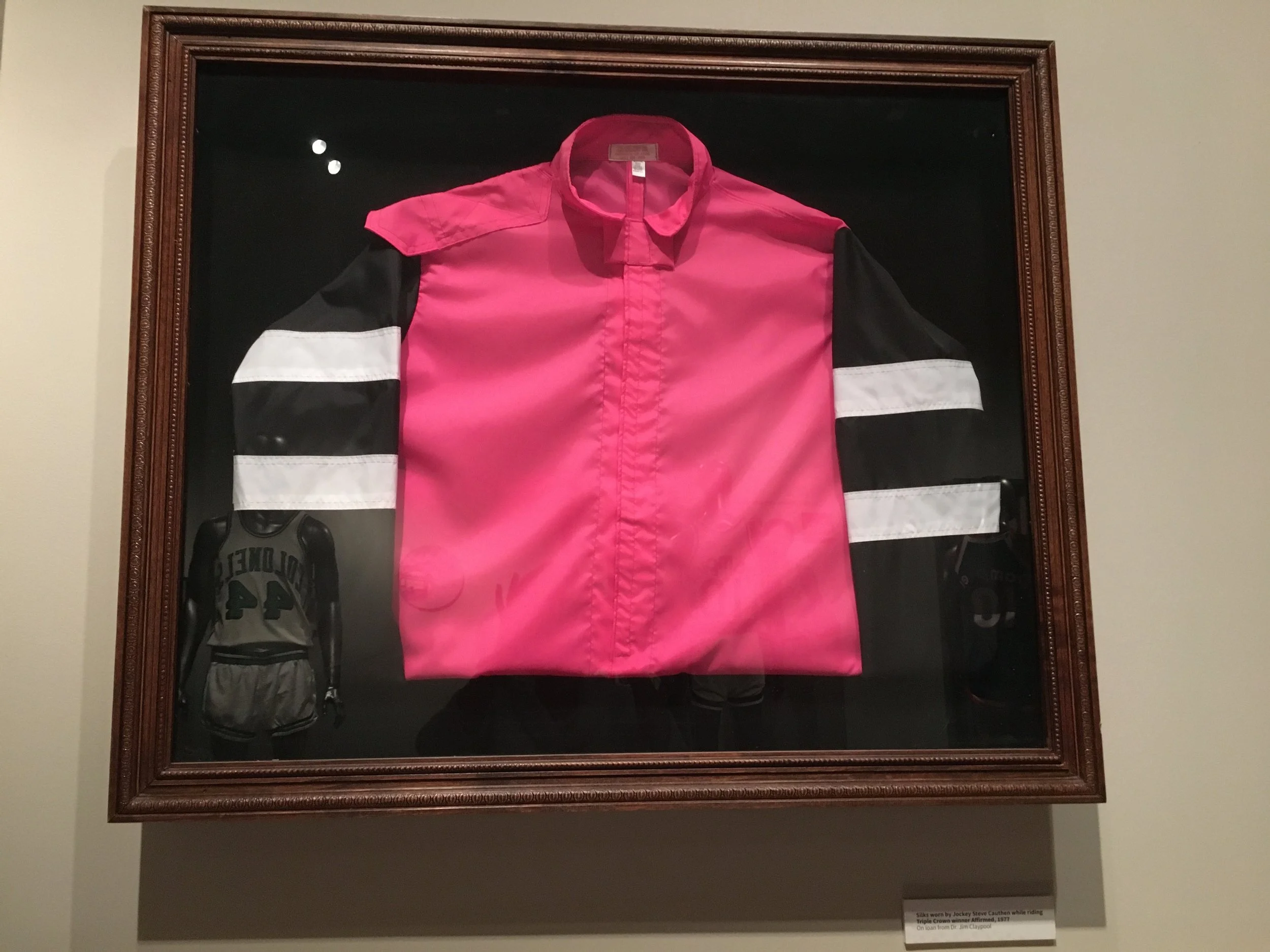

On this first Monday of May, our Frazier Weekly honors both Moms and Derby Day traditions. First, Vickie Yates Brown Glisson traces the connection between Kentucky burgoo and horseracing. Next, Northern Kentucky University professor emeritus of history Dr. James Claypool writes about 1978 Triple Crown–winning jockey Steve Cauthen. Replicas of Cauthen’s pink silks are on display in the Frazier’s Cool Kentucky exhibition—as are 2005 Derby winner Giacomo’s garland of roses, on loan from our friends at the Kentucky Derby Museum.

Sticking with the theme of Derby and Moms, Rachel Platt weighs in on Anita Madden’s Derby decadence and Casey Harden shares a letter a daughter in Georgetown, Kentucky, wrote to her mother during the Civil War. The letter will be featured in our soon-to-open exhibition The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall. Our new online Museum Store is selling Mother’s Day–related gear and Kentucky author (and mother) Emily Bingham shares some behind-the-scenes information from her new book, My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song.

I hope you enjoy.

Andy Treinen

President & CEO

Frazier History Museum

This Week in the Museum

The one hundred and forty-eighth running of the Kentucky Derby will be held on Saturday. Not only is the Kentucky Derby the most exciting two minutes in sports, but it is also steeped in history and tradition whether it is what to drink on Derby Day—mint juleps—or what to wear—a beautiful hat—or what to eat. The Derby has a number of culinary traditions that will be on full display at both local parties and Churchill Downs. These will likely include such Kentucky favorites as beaten biscuits with a thin slice of salty country ham, Benedictine sandwiches, Hot Browns, and Bourbon balls. However, one of the most popular food choices and a staple at the track is a concoction known in Kentucky as burgoo. It can be pronounced as either BUR-goo or bur-GOO, depending on which syllable you are inclined to accent.

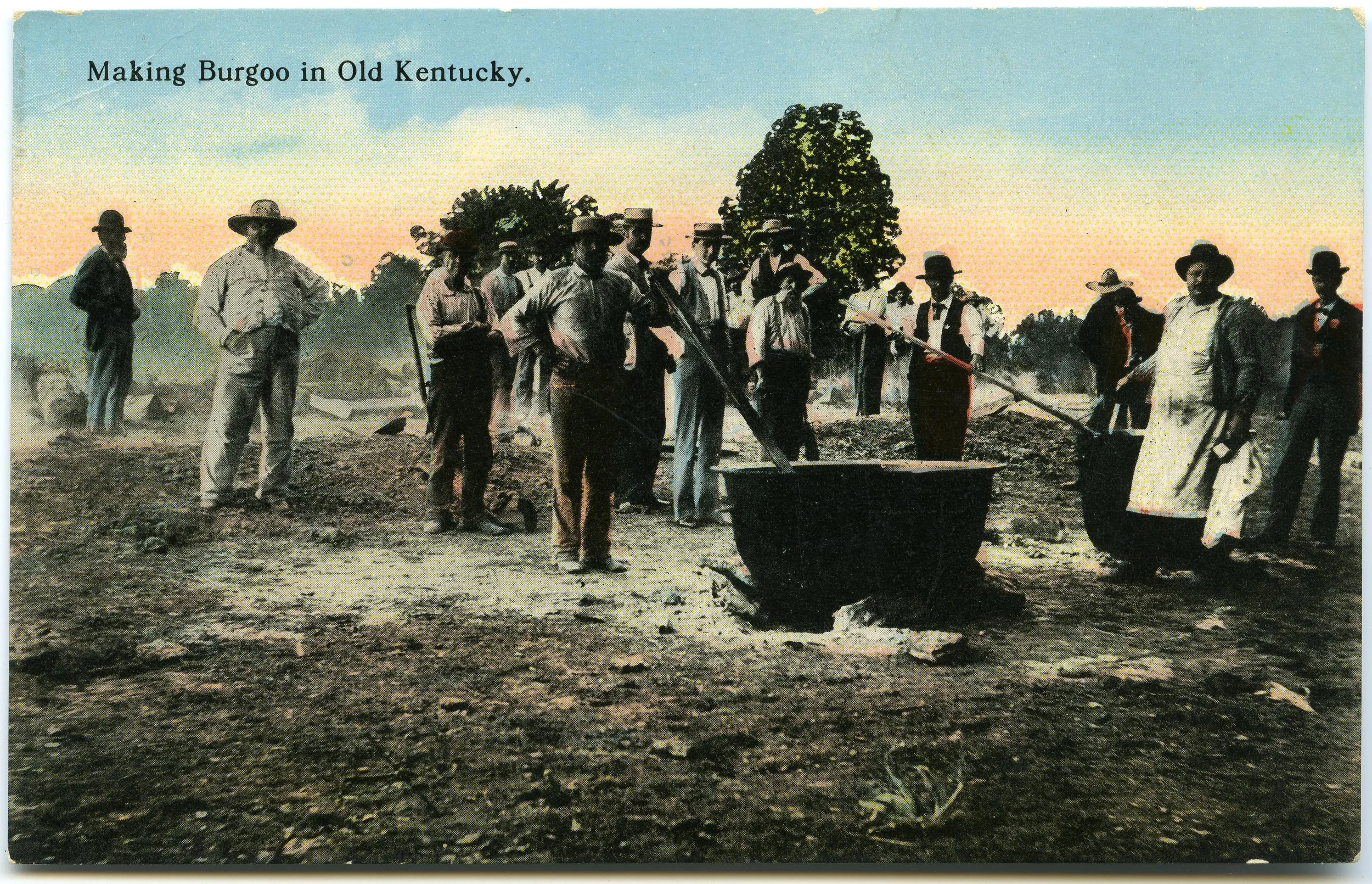

Postcard that depicts people making burgoo for visitors attending the formal opening of the Democratic Campaign in Kentucky, held in the city of Winchester, September 9, 1916. Handwritten note on verso reads: “Democratic Barbecue at Winchester, Sept. – 1916, Hughes & Wilson campaign.” Arrangements for up to 20,000 visitors had been made. After the burgoo was served, U.S. Vice President Thomas Marshall made a speech. Credit: Postcard Collection, University of Kentucky Special Collections.

If you are not from Kentucky, you may be asking: What is burgoo? Burgoo is a hearty, somewhat spicy stew made with a variety of meats, vegetables, and seasonings. The origin of burgoo is unclear. It is likely the stew was created as a warm and hearty meal of whatever meats, vegetables, and seasonings were available at the time. The meats that were originally used in burgoo may seem a little peculiar today: They included venison, raccoon, squirrel, rabbit, possum, and fowl—in other words, whatever a person was able to kill and add to the pot. Today, the meat is much tamer: It is likely to be some mixture of pork, lamb, chicken, and beef. The ingredients were usually cooked in water along with seasonings very slowly for hours over an open fire in large cast iron pots and constantly stirred with large paddles usually made for the job. The time and effort required to make the concoction meant it had be prepared in large amounts to serve huge crowds.

In Kentucky during the early 1800s, the dish became associated with the agriculture industry when it was served at livestock sales. From there, it was a natural transition to be served at horse racing events where folks gathered to socialize, compete, and buy and sell horses.

Photograph of the racehorse Burgoo King, May 21, 1937. Credit: Lafayette Studios Photographs: 1930s Decade, University of Kentucky Special Collections.

Throughout Kentucky, there were individuals who became known for their skill at making burgoo. Their recipes, each of which was different, were highly protected secrets handed down in families. One of the earliest legendary burgoo makers was Gus Jaubert, a saloon operator in Lexington, who at one time prepared 6,000 gallons of burgoo for a Louisville Civil War veterans’ reunion in 1895. Frankfort's Buffalo Trace distillery hired Jaubert to cook for its employees. Two of his big iron burgoo kettles are still on view at the distillery's Burgoo House. Before long Jaubert became known as “the Father of Burgoo” and was catering events across the state. Another noted burgoo maker was J. T. Looney, a grocer from Lexington, who became known as the “Burgoo King.” Mr. Looney was so popular that a racehorse was named for him: Burgoo King, who went on to win the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness in 1932.

When the Kentucky Derby was established in 1875, burgoo naturally made its way as a popular food option at the racetrack. Today, burgoo is an important part of the racing tradition at the Derby and at the Keeneland Racecourse in Lexington, where some of the qualifying races for the Derby are held. Since the 1930s, Keeneland has been serving the same recipe for Kentucky burgoo that is cooked for hours in an enormous kettle. The burgoo is so popular that Keeneland goes through between ninety and 100 gallons of the stew each week.

Bowl of Kentucky burgoo. Credit: Holly A. Heyser, Pinterest.

Ouita Michel, a popular restaurant owner in Central Kentucky who supports the local food movement, has been quoted as saying that “Burgoo is essential to Derby not because the meat is particularly flavorful or the presentation is uniquely ornate; it’s a dish that’s filled with so much memory.” She also noted, “It’s been made by so many different groups of people. That multidimensional story is what makes it special and an essential part of who we are in Kentucky.”

Since Burgoo continues to be an integral part of the horse racing experience in Kentucky, make sure to enjoy a bowl when you’re at the track. If hosting a Derby party, why not make a batch of burgoo for your guests? Make sure to offer cornbread, saltine crackers, or oyster-type crackers as a side. The key is to let the mixture cook for several hours. Keeneland’s version of burgoo that has been served at the track for years is set out below. Grab a bowl with your guests and join in on the singing of “My Old Kentucky Home” as the horses parade to the post.

Recipe for Keeneland Burgoo

Serving Size: 10–12

Ingredients:

1 cup celery, diced

1 cup carrots, diced

1 cup onion, diced

3 lbs. stew meat, cubed

1 tsp. ground thyme

1 tsp. ground sage

1 tsp. granulated garlic

1 tsp. ground oregano

1 (12 oz.) can diced tomatoes in juice

3 lbs. frozen mixed vegetables (corn, lima beans, green beans)

1 (7 oz.) can tomato puree

1 (7 oz.) can tomato sauce

1 lb. frozen okra, sliced

1 tbsp. beef base

1 tsp. Worcestershire sauce

1 tsp. lemon juice

1 tsp. Tabasco

1 cup sherry wine

1 cup red wine

3 lbs. potatoes, diced

Directions:

Brown stew meat with herbs and garlic.

Add remaining ingredients and cover with water.

Bring to a boil and then reduce to a simmer for a minimum of two hours, or until ingredients have been tenderized but do not dissolve. The potatoes should be “fork tender” but hold their shape.

Adjust seasoning to taste and thicken with cornstarch if needed.

Sources

“Immense Throng is in Attendance at Winchester: Formal Opening of Democratic Campaign in Kentucky.” Owensboro Messenger. September 10, 1916: 1.

James T. “Col. Jim” Looney, a Lexington grocer, known locally as the “burgoo king,” watched over a kettle of the regionally popular stew known as burgoo at the Blue Grass Fat Lamb Show and Sale at Clay Gentry Stockyards on June 22, 1946.

Smith, Loran. Spread Formation: Tailgating and Home Recipes From College Football Greats!

Recipe by Keeneland Racecourse executive chef Ed Boutilier. Adapted from Spread Formation.

Vickie Yates Brown Glisson

Board Members, Frazier History Museum

Guest Contributor

Dr. James Claypool on 1978 Triple Crown–winning Jockey Steve Cauthen

My friend Steve Cauthen is a world-class Hall of Fame jockey who also happens to be a first-class gentleman.

From left, Dr. James Claypool, his wife Sharon Claypool, and Steve Cauthen attend the Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs in Louisville, May 3, 2014. Credit: Dr. James Claypool.

I first met Steve in the mid-1970s when, as dean of students at Northern Kentucky University, I oversaw his successful completion of the GED test. Our mutual love for thoroughbred racing established an immediate bond, and I followed his racing career avidly thereafter. Moreover, the girl he would marry was a student at my university, and I knew several members of his immediate family, as well.

A highly intelligent man, Steve had dropped out of high school at age sixteen to begin his remarkable riding career. He would go on to win 2,794 races, including the 1978 American Triple Crown, on Affirmed, and thirty-seven international grade 1 races, among which were the 2,000 Guineas (1979), the 1,000 Guineas (1985), two Epsom Derbies (1985 and 1987), and the Irish (1989) and Italian (1991) Derbies. My most memorable experience with Steve was in 1994 when I accompanied him and filmed his induction into the Racing Hall of Fame at Saratoga Springs, New York.

Replica Affirmed silks on display in Cool Kentucky, April 25, 2022. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

The replica Affirmed silks shown in the Frazier Museum’s current Cool Kentucky exhibition were made by the wife of a retired jockey and acquired by private purchase. They are a part of my personal racing memorabilia collection. Steve currently resides outside of Walton, Kentucky, at his “Dreamfields” horse farm. There he breeds, sells, and on occasion races horses he has bred.

Dr. James Claypool

Professor Emeritus of History, Northern Kentucky University

Guest Contributor

Frazier Borrows Anita Madden’s 1980 Hot Pink Chiffon Suzy Creamcheese Gown

The Kentucky Derby Eve parties the late Anita Madden threw were legendary—and so were the lavish clothes she wore.

The Frazier History Museum has two of her dresses on loan: first, the gold dress she wore to her Derby Eve gala in 1978, which took place at Hamburg Place, her horse farm in Lexington; and second, the pink dress she wore to a celebrity roast in 1980, which the Frazier has just obtained.

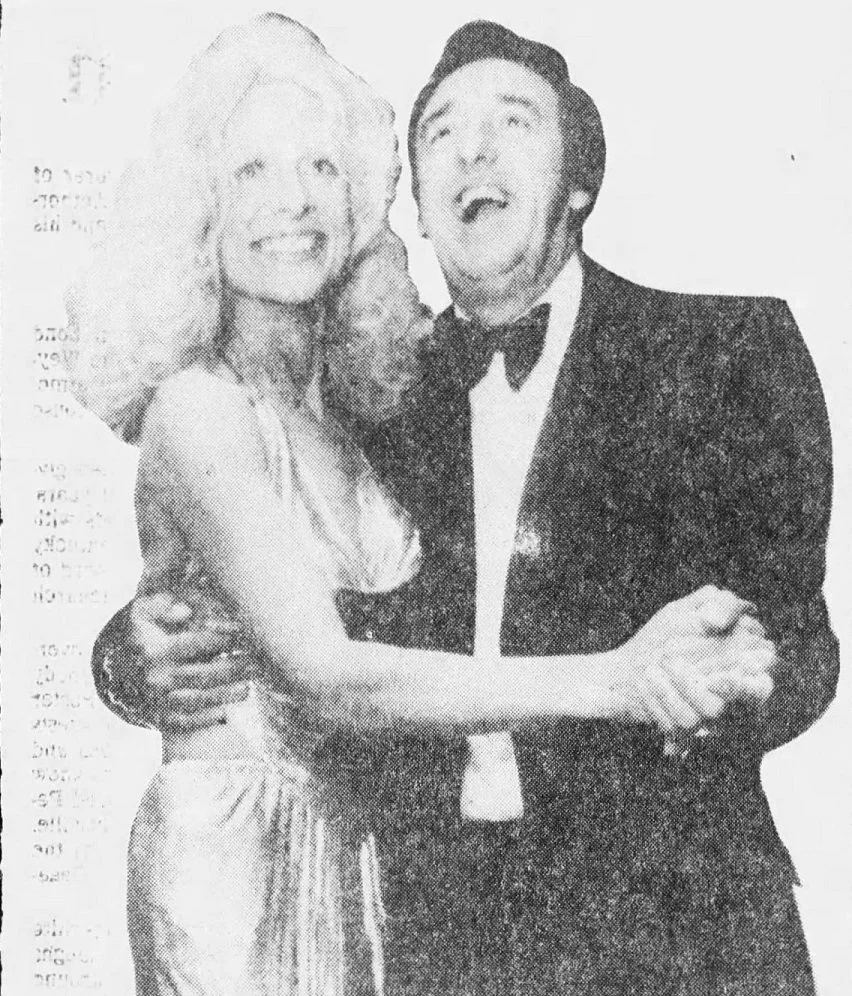

Detail of photo of Anita Madden dancing with one of her guests, Jim Nabors, during the annual Derby Eve party at the Maddens’ horse farm, Hamburg Place, in Lexington, Kentucky, May 5, 1978. The gold dress Madden wore at the gala is on display in the Frazier’s Cool Kentucky exhibition. Credit: Larry Spitzer, Courier Journal.

Anita Madden poses at the Anita Madden Charity Roast Tribute sponsored by the Lexington Jaycees at the Hyatt Regency Ballroom in Lexington, Kentucky, May 1, 1980. Designed by Las Vegas dressmaker Suzy Creamcheese, the hot pink chiffon gown with French baby marabou Madden wore at the roast is now on display in the Frazier’s Cool Kentucky exhibition, having recently been loaned to the museum. Credit: Highlands Museum and Discovery Center.

Madden was married to Preston Madden, grandson of horse breeder John E. Madden. The Maddens’ estate, Hamburg Place, bred racehorses, including 1987 Derby and Preakness Stakes champion Alysheba.

But Anita Madden was an influential figure in her own right.

From 1980 to 1983, following an appointment by Governor John Y. Brown, she served as the racing commissioner in Kentucky—becoming the first woman to fill that role.

From left, the gold dress Anita Madden wore at her 1978 Derby Eve gala and the pink chiffon gown she wore at a charity roast in 1980, April 22, 2022. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

From the 1950s to the ’90s, she hosted a Derby Eve party—an annual gala that came to be known as a who’s who of celebrity and over-the-top everything.

Let me just say: as a reporter for WHAS-TV, I covered some of those parties—and they were something!

But with that extravagance also came purpose: The parties served as fundraisers for the Bluegrass Boys’ Ranch, as well as other charities Madden supported.

If you’d like to learn more about Madden and see those two iconic dresses, they’re on display in the Cool Kentucky exhibition located on the first floor of the Frazier.

Sources

Buursma, Bruce. “The Madden crowd is far from quiet.” Courier Journal. May 7, 1978: 12.

Parks, Jim. “Anita Madden and roasters were really in the pink.” Courier Journal. May 2, 1980: C9.

Rachel Platt

Director of Community Engagement

Author Emily Bingham on the Material Culture of “My Old Kentucky Home”

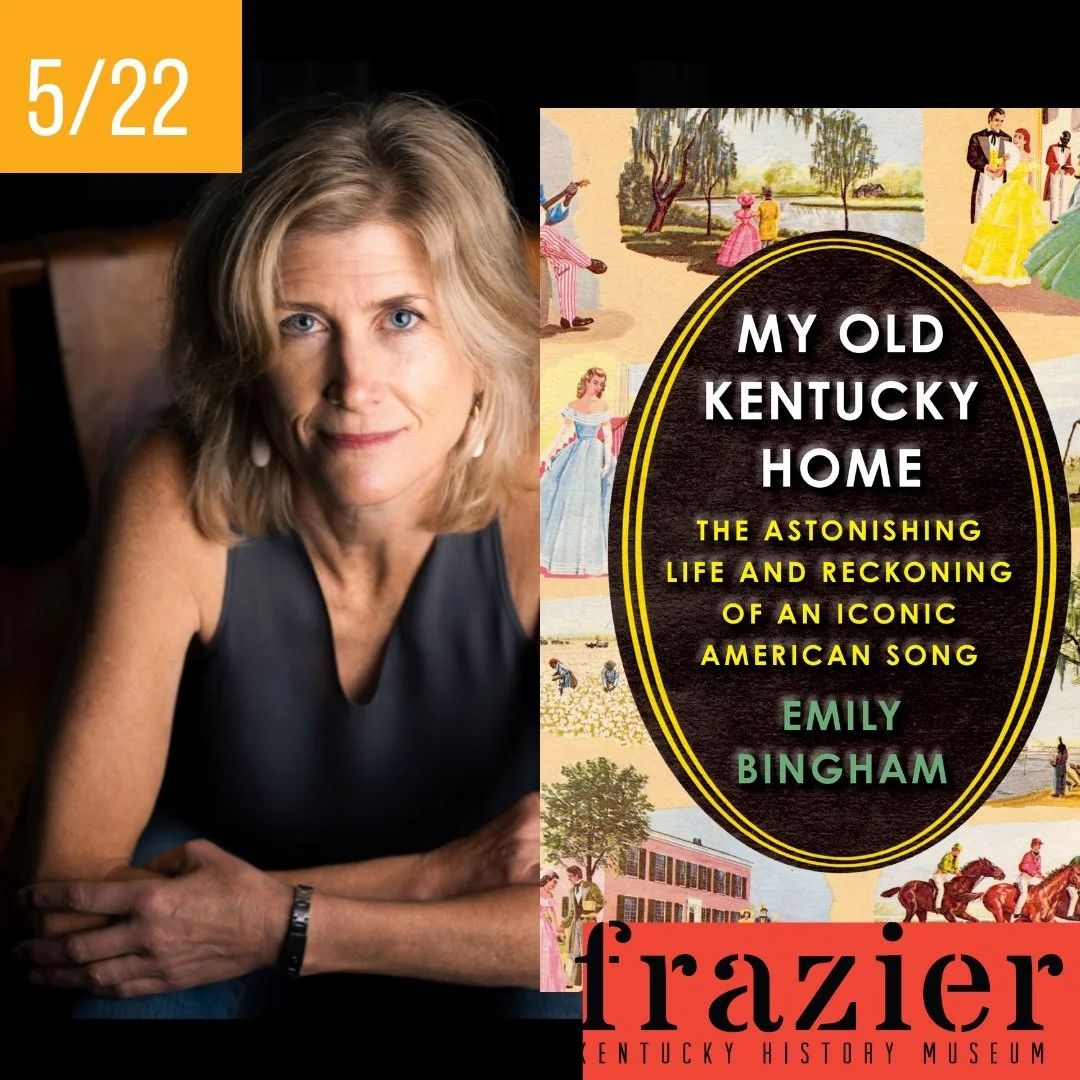

As we count down to Derby 148, a new book by author Emily Bingham that examines Kentucky’s state song—which is either sung or played before the Run for the Roses—will be released. Her book, “My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song,” digs deep into the full history of that song. Bingham will read from her book and take questions on Sunday, May 22, starting at 2 p.m. You can sign up for the program here. For today’s issue of “Frazier Weekly,” we asked her to write about her book and why it’s important to look closely at uncomfortable history.—Rachel Platt, Director of Community Engagement

There is no more thrilling part of making a book than what I call “the hunt.” If you look hard enough and dig deep enough, you will unearth treasures. For me, that looking happens mostly in archives and old newspapers.

“My Old Kentucky Home” is many things: a song published in 1853 by Stephen Foster, often called “the Father of American Music;” the official anthem of both the Kentucky Derby and the Bluegrass State; and a house museum in the community of Bardstown forty miles south of Louisville. I knew those things, at least in outline. I entered the archives to learn its history.

Blue and black “My Old Kentucky Home” garden flag. Credit: Christmas Central.

What I did not quite prepare for was the mountain of material culture the song has generated, the variety of objects that bear its stamp, ranging from predictable postcards and generations of songbooks to postage stamps, doorbells, bracelets, barware, garden flags, fried chicken boxes, bedding, and much, much more.

My biography of the song argues that “My Old Kentucky Home” was never just a song. It was from the outset about a man being sold for cash downriver from Kentucky to die in the sugarcane fields of the Deep South—a blackface minstrel tune featuring the trade in human beings. It says a great deal about this nation’s ability to ignore uncomfortable aspects of its history that this same song offered white Americans a soothing cocktail of sentiment and nostalgia for old times, papering over the realities of slavery and Jim Crow. (Click here to listen to singers performing the 1853 tune.) “My Old Kentucky Home” became a kind of sonic monument—white America’s song to itself.

Music enters us, becomes part of our breath, and this song is sung en masse each year at the Kentucky Derby by 150,000-plus spectators. It rings out on state occasions and at University of Kentucky basketball and football games (which one might mistake for state occasions). Over the years, I have grappled with the ways this haunted melody became ensconced in actual homes, morphing onto things that were touched and held close, ornaments caressed by millions of hands and eyes and lips. These may seem banal, but I believe they too make deep impressions.

I couldn’t fit these items into the pages of my book. They could easily fill a small museum, and perhaps the Frazier will one day undertake an exhibition. But I wonder: what is missed when the story of “My Old Kentucky Home” is told without accounting for its physical manifestation in everyday lives and its presence in the consumer culture? How has the song’s meaning been shaped by the way it has been acquired, possessed, collected, and worn?

The economy of its creation and dissemination involved Foster, perhaps the first American professional songwriter, being paid two pennies (about eight percent) as a royalty on each copy of official sheet music of “My Old Kentucky Home” that was sold. (Nobody could control pirated editions.) Scholars estimate nearly 70,000 copies were bought in the first decade, but that was not enough to keep him afloat. Foster, thirty-seven, died in Bellevue Hospital in New York City during the Civil War with thirty-eight cents to his name. Of course, his music publishers made a great deal more money off the song, as did the blackface minstrels who performed it to audiences across the country and the globe.

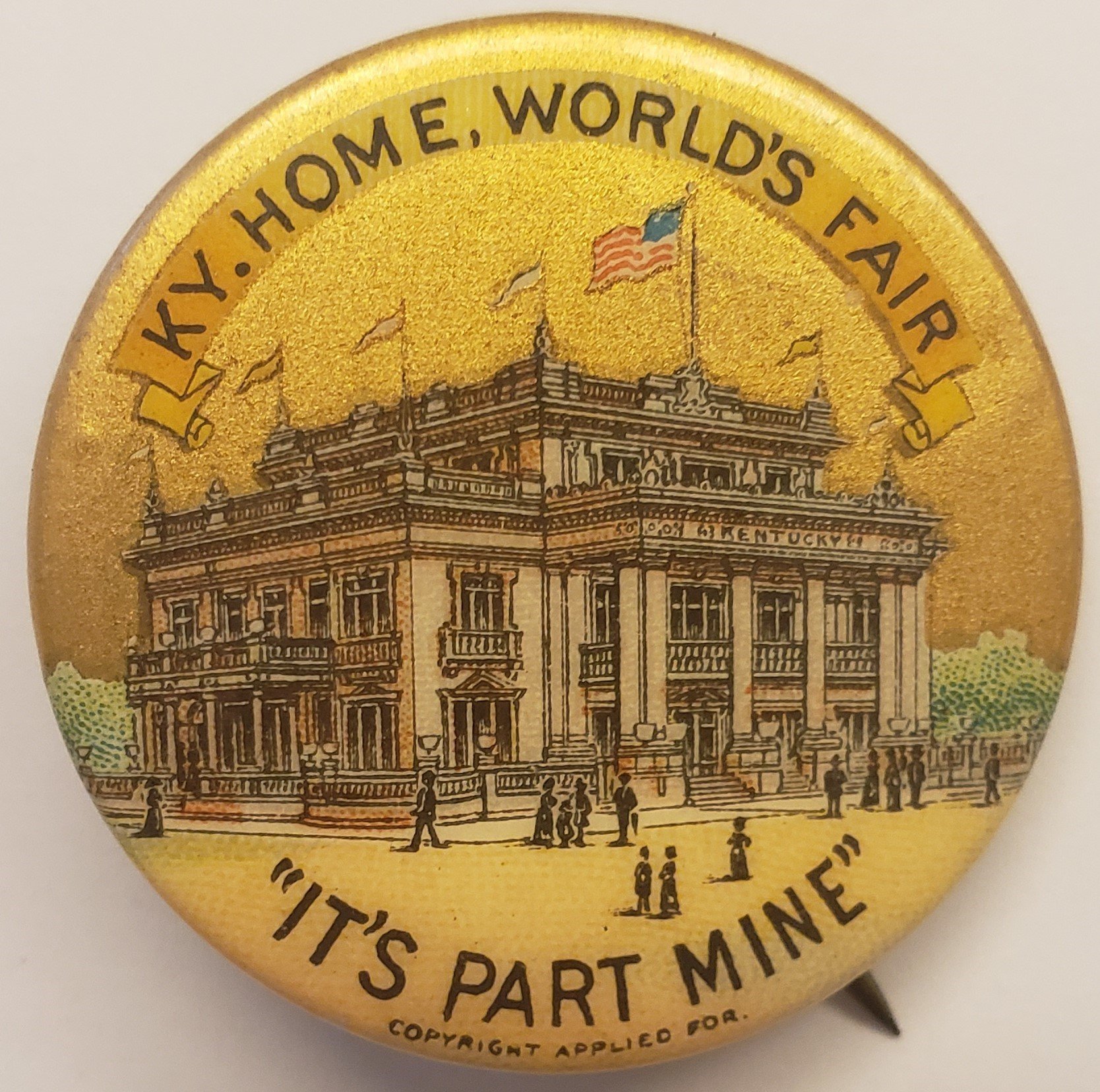

Button made in 1904. Credit: Emily Bingham.

Kentucky didn’t make much of the melody at all until fifty years later, when Jim Crow segregation was taking hold in the nation. The largest physical manifestation of the song surely was the Kentucky building at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, which deployed the tune as a brand to attract people and their money. Foster’s music floated out of the wide open doorways every hour of every day. Thousands of visitors left with printed copies of the melody as keepsakes. Souvenir buttons invited everyone to feel they owned at least a symbolic piece of the place: “Ky. Home—World’s Fair—‘It’s Part Mine.’”

Kentucky seemed to give freely of itself and its hospitality, and more people visited the state’s building that showcased its culture and economic promise than any other outside Missouri’s. White America was embracing (or at least tolerating) racial segregation, racial terror, and disfranchisement. It was time to let Civil War bygones be bygones and get back to business. A familiar sentimental song that invoked a Kentucky plantation set the ideal mood. “My Old Kentucky Home,” one observer noted at the time, brought a poor state “more publicity than any other one thing.”

Compact case, undated. Credit: Emily Bingham.

Two decades later, Foster and his song were officially enshrined when the Old Kentucky Home opened as a tourist attraction in Bardstown. Visitors from everywhere came to see “the home” that (according to myth) gave rise to this “immortal melody.” And they could take a piece of the myth home with them in the form of ashtrays, matchbooks, and compact makeup cases like one a friend sent me after a visit to an antique mall. Someone held it in her palm and used it to feel more beautiful before clicking closed its pink enamel cover and slipping it into her purse.

The Kentucky Historical Society has metal shelving reaching into the rafters to hold bits of the state’s physical patrimony. One item is a framed counted cross stitch pattern from 1980. The song’s original lyrics, “The sun shines bright on the old Kentucky home / ‘Tis summer, the darkies are gay” waft above the iconic brick Bardstown house sewn in red. The song was literally stitched into the thoughts and feelings of the person who completed the pattern.

Sheet of “My Old Kentucky Home State Park” stamps made in 1992. Credit: Emily Bingham.

Part of writing my book became about my own entanglement with the song that looms so large in my state’s life. While planning my wedding in the mid 1990s, I got to select the stamp for the invitations. An almost childlike, sunny depiction of the house in Bardstown had been created to honor the state’s bicentennial, and once the invitations were printed, we sat with a damp sponge and sheets and sheets of perforated paper, gently tearing and wetting and sticking them on, our fingers smelling of US Postal Service glue. The stamp’s stately and cheerful scene adhered to happy anticipations of a special day long before I knew what “My Old Kentucky Home” was about.

Ceramic plate from Stephen Foster Series by Willoughby Ions, courtesy Center for American Music, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Foster hailed from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and one of the most fruitful sources for my book about his song was the University of Pittsburgh. Over the course of a decade, the Indianapolis pharmaceutical executive J. K. Lilly spent millions collecting and disseminating everything he could find about the songwriter. He called it “Fosteriana” and gifted the collection to the school in Foster’s home city. I spent weeks at “Foster Hall” at a library table groaning with everything from letters to letter openers, drinking glasses to magical glass lantern slides that projected the “story” of “My Old Kentucky Home.” But my hands nearly shook when I pulled from a box a pastel-colored plate dated 1941.

The chorus to “My Old Kentucky Home” goes like this:

Weep no more, my lady,

Oh! weep no more today!

We will sing one song

For the old Kentucky Home,

For the old Kentucky Home, far away.

The figure of the “lady” hovered in my mind from my earliest memories of the song. Who was she, I wondered? When my husband first came to Kentucky at Derby time, he was struck by the hoop-skirted women who greeted air travelers with baskets of Bourbon-laced bonbons. The antebellum atmosphere seemed to stretch across the weekend, with that lady of the chorus as a sort of center pole.

A logical reading of Foster’s lyric might suggest that the “lady” was the enslaved man’s beloved back in Kentucky, and he sings to her, from the Deep South where he will die in the fields, of bygone days when they were together. This might sound sympathetic, but blackface only laughed at Black “ladies”—who were cross-dressing white men in cork. Another interpretation might suggest that the “lady” was the “mistress” of the plantation, someone who dressed like the women in the Louisville airport. But intimacy between a Black man and a white woman was an even more mine-filled potentiality than a “lady” who was enslaved.

Enter artist Willoughby Ions of Richmond. In 1941, she created a hand-painted series of Stephen Foster dinnerware, which sold in an upscale Manhattan department store. For “My Old Kentucky Home,” she depicted a white “lady” in a garden or grove, with a big house in the background. She cries into her handkerchief. A Black man kneels at her feet, pleading with her to “weep no more.”

The shorthand of an object conveyed what few were willing to express in so many words: that a white songwriter’s imagined depiction of a man sold away from his family to die was never really about the people it purported to be concerned with. It was about the satisfactions, hierarchies, and sentiments of the race that created and staged and bought the song.

Who ate off these plates? Did they hang in peoples’ homes? Someone dusted, soaped, and dried them over years. The plate’s charming style reveals a brutal reality about “My Old Kentucky Home” and gender and race in America. It unlocks the ugliness of what for generations was expected of Black people when it came to white feelings.

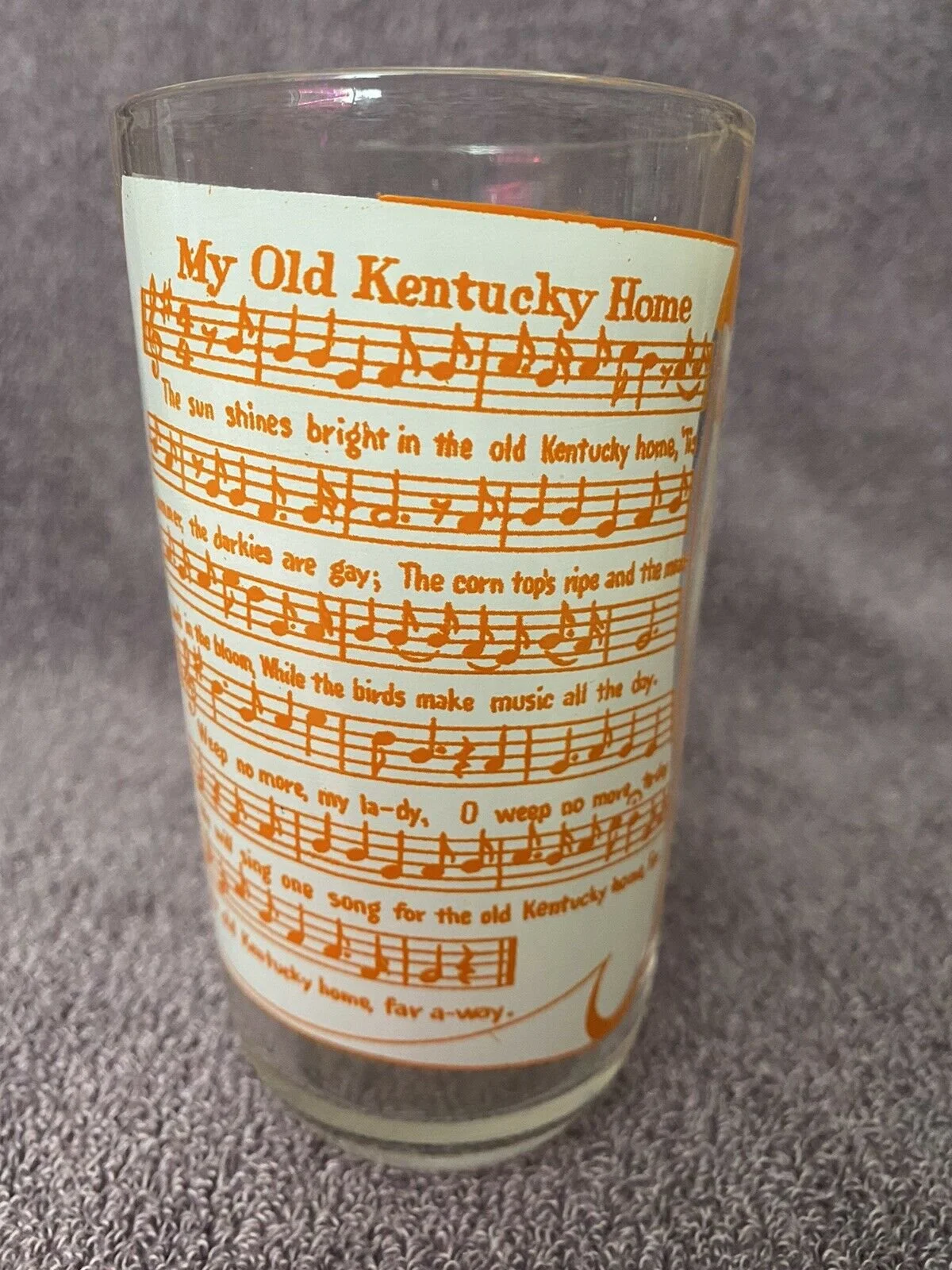

Vintage Hazel Atlas “My Old Kentucky Home” Big Top drinking glass made in the 1950s as part of a peanut butter promotion. Credit: find42, eBay.

Finally, the most common single category of three-dimensional representations of “My Old Kentucky Home” seems to be vessels for beverages. There are shot glasses, jiggers, old fashioneds, double old fashioneds (highballs), coffee mugs, julep cups, and even a whiskey decanter created by the distillery Heaven Hill. A person can can toast, cheer, slake their thirst, mix a cocktail, or cozy up with any of these commemorative containers. Why the ubiquity? There’s an association with Kentucky’s signature spirit, Bourbon, of course; but is it a stretch to say that, for coming on a century, we have swallowed a song about slavery as Kentucky’s brand?

Emily Bingham

Author, My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song

Guest Contributor

Countdown to The Commonwealth: Mollie’s Letter, May 23, 1862

Logo for The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

Each week leading up to the opening of the Frazier History Museum’s next permanent exhibition “The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall,” we will highlight an object or objects to be included in the exhibition.

Opening with a private reception May 19 and to the public June 1, 2022, “The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall” will tell the story of Kentucky’s rich history, including, among other topics, its native peoples, the Civil War, and the early nineteenth century, when cities such as Louisville gained prominence due to their important locations along the Ohio River. It will expand viewers’ personal connection to history by pairing historic figures like Henry Clay, emancipationist Cassius Clay, and Abraham Lincoln with diverse narratives from lesser-known figures in Kentucky history.

In partnership with artist Ché Rhodes and the (Un)Known Project, led by artist-run nonprofit IDEAS xLab, the exhibition will include a space for visitors to reflect on the stories, both known and unknown, of the enslaved that lived in Kentucky. This interactive exhibition is designed to engage visitors of all ages and will feature objects related to Kentucky’s diverse history as a border state on the banks of the Ohio, including the clock face from the top of the Town Clock Church in New Albany, Indiana, an important stop on the Underground Railroad, and the Bloedner Monument, the oldest surviving memorial to the Civil War.

“The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall” has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.—Amanda Briede, Curator

Letter a Georgetown, Kentucky, resident named Mollie wrote to her mother on May 23, 1862. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

Chosen for the Mother’s Day issue of Frazier Weekly, the Mollie letter proves the state motto of Kentucky—“United We Stand, Divided We Fall”—has always applied to Kentuckians and their mothers.

On May 23, 1862, a loving daughter in Georgetown, Kentucky, named Mollie wrote this letter to her mother, whose address is not known. “My Dear Mother,” it begins. “How I miss our mails! After hearing nothing for many days, at last the long-expected letter came, and my heart was made inexpressibly lighter, except that its made me very homesick and kept me crying for a half hour.”

In the letter, which spans eight pages, Mollie describes her day-to-day life and social visits from her close friends. She also goes into detail about how much she misses her mother, although her mother has only been away visiting family for a couple of months. Mollie talks to her mother about decisions she must make regarding a number of things, such as job opportunities. She says she may not be invited back to the schoolhouse after the school year ends and that she does not enjoy children, so being a governess would not be a good fit, either. She is also uncertain about a gentleman who is courting her friend, and reports that her friend has nothing good to say about the man, but still wants her to think well of him.

“My candle is sinking and my eyelids too,” the letter concludes. “Good night dear mother when I get home again I will always stay with you. [Enjoy?] yourself see you can. And still love your loving Daughter Mollie.”

Mollie wrote this letter prior to pivotal moments in the Civil War: The war had broken out in April 1861, and Confederate forces had occupied towns in Kentucky since September 1861; but it would be another two months until July 15, 1862, the day Confederate Gen. John Hunt Morgan would raid Georgetown, where Mollie lived. Had the stress of the war not affected Mollie yet, or was she trying to continue to live a normal life during this hard time? These are questions whose answers we don’t have.

What we can understand, however, is the close relationship between these two Kentuckians—and the love they shared.

Casey Harden

Director of Exhibit Ideation

Museum Store: “Call Your Mom” Pot Holder

“Call Your Mom” pot holder sold in the Frazier’s Museum Store and available for order online. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

This is a gift for you that is really a gift for Mom. This “Call Your Mom” pot holder is a life hack: Every time you cook something on the stove, you’re reminded to call your mom. Purchase online and don’t forget to call the Moms in your life this Sunday.

Across the Universe Summer Camp to Explore Muppets, Magical Realism, and More

Wow, it’s already May, and by the end of this week our city will have hosted the one hundred and forty-eighth Run for the Roses. That means it’s only a month until summer camp season! Have you signed your child up yet?

Summer campers pose in The Lewis and Clark Experience, 2019. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

One way we love to engage with kids is through their own interests. That’s why we created the camp Across the Universe (I hope my fellow Millennial parents appreciate the name!). This is a fun week of celebrating fans, fandoms, and the history behind them. We all learned that we don’t talk about Bruno, but did you know that the magical realism found in movies like Encanto can be traced back to the literary genre perfected in Latin America? What are the real legends upon which Percy Jackson is based? Do you have what it takes to be the Swedish Chef? You can find the answers to these questions and more during this camp, which we will be offering twice this summer: June 27–July 1 and July 18–22. This year promises to be extra fun, as we curated our themes based on feedback from our winter break campers.

This is always a best seller, so register today!

Heather Gotlib

Manager of Youth & Family Programs

Membership

Happy Mother’s Day to All of Our Frazier Family!

With Derby on the horizon, don’t forget that Mother’s Day is the day after Derby this year. So treat those mother figures in your life: Why stop at just a day when you can make this month all about that special person? Attend our Summer Book Club together reading the NEW RELEASE: My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song by Emily Bingham. That sounds like a fantastic idea!

Graphic for Mother’s Day 2022. Credit: Frazier History Museum.

Cue another amazing Frazier gift idea!

Book Club Member Perks for our May Title:

ALL members are welcome to participate in this program.

Early access to purchase the book.*

Book available at a special discounted price.

Members and (1) guest may be included in your RSVP.

Casual visit to a portion of our meeting by the author.

Reserved priority seating to the reading and Q & A following our meeting.

Be one of the first in line to get your copy signed by the author following the Q & A.

Advance notice of our June title announcement.

For each monthly meeting you attend, you will get a chance to win a door prize at the end of the Summer program.

*Access given once we receive your RSVP. Limit of 2 books sold per account before May 22.

Details You Need to Know:

RSVP to aegan@fraziermuseum.org by May 10.

Our kick-off meeting will take place on Sunday, May 22, at 1 p.m.

Your RSVP to the Book Club will serve as an RSVP to the reading and Q & A.

Click here to find more details about the book, public reading, and Q & A program.

Find more information about our Summer Book Club here.

Is that mother figure not already a member to the Frazier? Then forget a gift just for the day or even the month: Give them a gift for THE WHOLE YEAR!

Purchase a gift membership! As little as $20 will allow them access to member-exclusive events throughout the year!* Did I mention that for the $20 Individual membership, they would also get year-round access to the museum, a 10% discount in the museum store**, and discounted parking!?

*Not all member-exclusive invitations apply to the Individual and Family membership levels.

**Exclusions apply.

Gift an experience!

Amanda Egan

Membership & Database Administrator